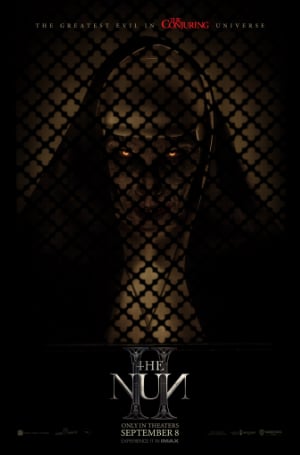

Part of “The Conjuring” franchise, the recent horror film release of The Nun II offers a tantalizing experience of the reality of evil in the world only overcome by faith and the grace of God. Directed by Catholic filmmaker Michael Chaves (The Curse of La Llorona, The Conjuring: The Devil Made Me Do It) and produced by Peter Safran and James Wan, The Nun II steps up a notch from its predecessor The Nun in the use and understanding of Catholic imagery. It also represents religious life in a surprisingly accurate depiction of consecration to Christ, though a bit muddled on the ministry of exorcism, which would be reserved to priest-exorcists.

I’m not a fan of horror, but so often supernatural horror can only be explained by Catholic imagery and symbolism because it deals with “the mystery of faith,” something William Friedkin (The Exorcist, 1973) acknowledged explicitly in his film. To do that, it shows evil, and in supernatural horror, it shows the workings of the devil in and through those possessed. Evil is real and that’s an important acknowledgment in a culture that often denies the existence of the devil, even though the visual medium of film shows it in crazy, bizarre ways. Saint John Paul II in his Letter to Artists understands artists’ depiction of evil when he says, “Even when they explore the darkest depths of the soul or the most unsettling aspects of evil, artists give voice in a way to the universal desire for redemption” (no. 10). In The Nun II redemption is offered for more than one of the characters. It comes through invoking the name of God, the Holy Spirit, depicting the crucifix, images of Mary, the rosary, relics of the saints, and acknowledging the Eucharist as the means to overcome evil. In a true exorcism, that is what priest-exorcists use—the name of God, Jesus Christ, Mary and sacramentals that reflect the presence of Christ, the One more powerful than the devil. The Sacraments of Confession and Eucharist are the surest means to overcome evil.

Following up on the first film, Sister Irene (Taissa Farmiga), now a professed religious sister, has a dream about her friend Maurice “Frenchie” (Jonas Bloquet) who saved her from death in their encounter with the demon-nun a few years prior. Seemingly possessed by the devil, he calls out to her, “Save me, Sister!” She wakes up and is summoned by the bishop to go and investigate the demon-nun who has reappeared at a Catholic Church in France by burning a priest at the foot of the altar. That follows upon multiple suicides of priests and nuns around Europe. The bishop tells Sister Irene, “You performed a miracle once. The Church needs another.” Let me just say that this is quite fantastical storytelling and not exactly how possession or oppression work and the suicide element is excessive. Also, God performs miracles, not human beings. And only priests are exorcists because they have a sacramental seal through the Sacrament of Holy Orders that gives them another line of defense against the devil.

Sister Irene tells the Novice, Sister Deborah (Storm Reid), that she has been called on another mission. Sister Deborah has her doubts about faith and says her mom was “her church,” meaning that she grounded her. Yet, her faith, especially in the Eucharist is on the edge. Sister Irene tells her, “It’s an act of faith…to believe in the Body and Blood of Christ.” This acknowledgment of the Eucharist as the true Body and Blood of Jesus Christ is significant to the rest of the story. Even though only the words of consecration of the bread and wine can be done by an ordained priest, the film confesses that the Eucharist brings humanity redemption and salvation. That means, only Christ can overcome the devil, not human beings on our own.

Sister Irene goes on to say that the saints who have gone before believed in something greater than themselves and tells Sister Deborah, “I hope you can find your faith when the time comes.” What I like about this film is that is expresses that we all have a test of faith to face in our life. We have free will to choose the good or to choose evil, to believe or not to believe. When facing the demon, only faith in God gives us the strength to overcome it. Sister Irene goes to France and Sister Deborah sneaks behind her to be with her. They end up at a girls boarding school to confront the demon-nun who has wreaked havoc on the inhabitants. It is there that she sees Maurice who is employed as the handyman. This is the point where the horror elements take over, so I leave that to your imagination.

Throughout the film, the story and imagery of Saint Lucy, patron of the blind, reveal a deeper meaning to the story. The schoolgirls tease the teacher’s daughter, Sophie, and dare her to “defy the devil” by staring into a stained glass with an image of a goat. They tell her that when the light shines in the right place the goat’s eyes turn red and the devil is looking at her. Sophie becomes the one to discover that something is present “that’s not meant to be here.” When Sisters Irene and Deborah arrive, they discover that the demon wants the holy relic of Saint Lucy’s eyes, and the victims have all been her decedents. The relic is buried somewhere on the property of the school.

When I asked the director Michael Chaves why Saint Lucy, he said, “It’s about seeing in all the various ways and seeing ourselves as we really are…Irene doesn’t want to really look at her past, at who she really is, recognizing the good things and bad things about herself.” He explains that “She is on this quest to see [and] to find the eyes of Saint Lucy.” Medieval images of Saint Lucy picture her holding her eyes on a platter or in her hands. This plays off of her name, which means “light,” and so she became the patron saint of sight. A virgin and martyr from the early 4th century, Lucy was born in Syracuse (Sicily) and dedicated her virginity to Christ as a young woman. An angry suitor accused her of being a Christian and she was sentenced to death during the Diocletian persecutions. As patroness of sight, Saint Lucy leads us to consider the eyes as the window to the soul. The eyes reflect the goodness or the evil present in the characters, including the demon-nun whose piercing yellow eyes reflect the devil’s anger at all who prevent it from finding the relics. I’m not exactly sure of the reason the devil wants the relics and why it stops at nothing to get them. In reality, the relics reflect the characters’ faith in God.

Chaves explains that “The whole Conjuring series is a conversation about faith and the different forms it takes.” Each character must confront his/her own soul about his/her faith. Those who do, begin to see in a new way, and faith enlightens their path going forward. “There is an urgent need,” says Pope Francis, “to see once again that faith is a light, for once the flame of faith dies out, all other lights begin to dim. The light of faith is unique, since it is capable of illuminating every aspect of human existence. A light this powerful cannot come from ourselves but from a more primordial source: in a word, it must come from God” (Lumen Fidei, no. 4). The horror film The Nun II, as a storytelling medium, shows that faith matters and when we have faith our path is filled with light, God’s Light who is Christ, our Way, Truth, and Life. Only in him can we overcome the fear that evil and darkness create. Only with the eyes of Christ can we see how a horror film expresses that good always overcomes evil and faith transforms fear.

NOTE: If you are a fan of horror movies, you may find this film intriguing. If you are not a fan of horror, then other films may be more to your liking.